The ABC's of Hammers

- Gray Tools Official Blog

- 20 Dec, 2018

Many tools in a tradesperson's toolbox are designed to “take a beating; hammers by definition belong in this category.

The history of the hammer dates back to ancient times. The Romans, who invented the forged iron nail, used the claw hammer as a dual-purpose tool for pulling and pounding nails. A simple tool by design, a hammer consists of two basic components: the handle and the head.

The quality of the material used for these components, and the proper head-to-handle weight distribution, make the difference between a quality striking tool and one that can pose a user safety risk.

When selecting the right hammer for any given application it is important to pay attention to the following:

Head

The head is the component exposed to impact; hence its importance in the durability and overall quality of the hammer.

The quality of material used to make the head is an important factor in producing a head that will withstand many years of repetitive use. For heads made of metal, achieving the correct hardness through a process called heat treatment is also very important; a head that is too hard will be brittle and chip easily. A head that is too soft will dent and deform easily.

Hammers of the same type are offered in a variety of head weights (usually expressed in ounces, pounds, or grams). For example, a ball pein hammer can range in head weight from 4 to 48 oz. Lighter hammers are used for tasks that require more finesse, precision and control, while heavier heads are employed when more force is required.

Most hammerheads are made of steel, which provides the required durability and impact resistance. Speciality hammers are made of various materials, such as plastic (soft face hammers), titanium (weight reduction), stainless steel (to avoid object contamination) or brass (to avoid sparks), depending on the hammer style and application.

Head functionality, although not always obvious to the untrained eye, are designed to accomplish much more than the basic task of driving a hammer into an object. Additional functionalities include the ability to pull or hold nails, pry wood boards apart, or shaping metal.

Handle

The handle is the component which connects the user to the tool. It greatly influences user comfort, while also playing a key role in the tool's overall strength, durability, and function. The most popular materials used are wood and fibreglass.

Wood is the traditional material used in handle construction. When you think of a hammer, you typically picture a steel head and wooden handle. Wood has two major advantages over fibreglass.

First, wood is able to absorb shock very well, which makes it is more comfortable to operate. Second, professionals agree that hammers with wooden handles are better balanced than fibreglass ones allowing for smoother swings.

On the downside wood will eventually rot, warp, break, shrink and become loose, especially if not maintained properly.

Fibreglass handles have become the new trend in hammer construction, to the point where some manufacturers have stopped offering wooden handled hammers. The main benefit of fibreglass handles is durability; the handle will not shrink, warp or rot, and is almost impossible to break.

The main disadvantage of this type of handle is the shock absorbing capabilities, which are not on par with its wooden counterpart. Although many manufacturers have implemented anti-vibration technologies for better shock absorption, wooden handles are still considered superior in this regard.

Regardless of the handle style, a quality hammer is properly balanced, with proper weight distribution between the head and the handle to allow smooth, effortless, and repetitive swings with very little effort.

Handles are typically connected to the head in one of three ways; mechanically, chemically or a single unified piece. Mechanical bonding means a physical component such as wedge or fastener are used to fasten the two components. In a chemically bonded hammer the handle and head are fastened solely with the use of resins such as epoxy. A single piece hammer does not have bond but is rather made from a single piece of metal, where the handle and head are seamlessly unified. In some rare exceptions, particularly in sledgehammers, manufacturers may use a double method of mechanical and chemical bonding to achieve a superior and unique connection.

The length and shape of the handle play an important role in the function of any striking tool. The longer the handle the larger the force generated for strikes. Conversely, the longer the handle the less control the user has. Handles can also future grips of various shapes, sizes and materials all designed to improve grip, increase comfort or dampen vibration.

Types of Hammers

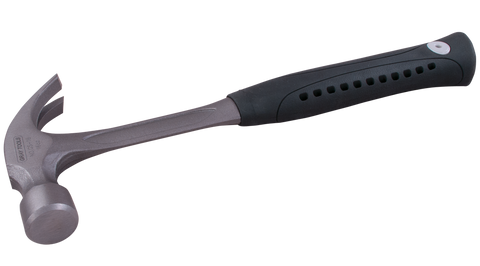

Claw hammers - as the name suggests, feature a claw at one end for pulling nails, and a striking face at the other end to drive nails typically into wood. The forged bevel allows the claw to slip under the nail for easy removal. Some models feature a dual bevel, the second bevel providing a secure grip of nails of various sizes.

The edge of the striking face is also beveled to avoid chipping during off-centre strikes. The striking face is smooth and slightly domed to avoid marring of the work surface and correct off-centre strikes.

Claw hammers are usually lightweight, with head weights ranging between 10 to 16 oz, tailoring them to the size of nail to be driven or project being completed.

Framing hammer - although similar in appearance to the claw hammer, this hammer has some distinctive features that make it suitable for the demands of framing.

A framing hammer provides more force than accuracy. The head is heavier than the typical claw hammer, averaging 20 to 25 oz and the handle is longer, helping to drive nails with fewer strikes. The striking face is waffled, helping to prevent accidentally bending of nails. The claw end of a framing hammer is straighter than claw hammers, ideal for prying wood boards apart. The head features a grove and/or magnet for nail setting, which allows users to drive nails with one hand.

Ball pein hammers - also known as machinist hammers, are using in metalworking to mould sheets of metal in various shapes and directions. The head features one hemispherical end for metalworking and one flat face for driving nails. The head weight ranges from 4 to 48 oz, depending on the application. The flat end is used for driving nails, punches and chisels, or setting rivets, while the ball end is used for shaping metal.

Rubber mallet - is a must have tool in any shop. In the event damage to the work piece is a concern, the use of a hammerhead made of moulded rubber helps. Rubber mallets are used in outdoor projects such as interlocking installation, since the head does not cause damage to the interlocking piece, and light tapping sets them in place. Rubber mallets are lighter and more versatile than claw and ball pein hammers and typically have a large round striking faces.

Sledge Hammers - is much heavier and bulkier than your typical hammer, and not often used outside construction and demolition applications. Typical uses include concrete slab removals, stake driving, and various demolition jobs. Always wear protective gear and allow for adequate clearance when swinging a sledgehammer. Due to the long handle and heavy head, overstrikes are commonplace. Repeated overstrikes can pose a workplace danger as strikes to the handle and head can lead to injuries.

Soft Face hammer - another type of hammer to use when non-marring is important, such as cabinetry and other fine woodworking work. Soft face hammers feature tips made of plastic or rubber, nylon and other soft compounds and are replaceable. You can buy a kit of replacement tips that includes ends of different hardnesses, suitable for a wide variety of applications.

Specialty Hammers - these hammers are uniquely designed to tackle specialised jobs. Specialty hammers include mason’s hammer (designed to cut and set bricks), drywall hammer (for cutting and installing drywall), upholster or tack hammer (designed for driving tacks in upholstery work).

How to Properly Use a Hammer

Given its basic design and widespread use, the untrained might think that using a hammer means pounding at the piece until the work is done. This “beginner technique” often leads to unnecessary damage, a tired arm, and serious injury. Professionals are able to select and use the correct hammer for the task, and using it repetitively without tiring their arm.

The following procedure should lead to a quality “hammering” job:

- Get a good and secure grip on the handle. For jobs that require precision and control, grip the handle closer to the hammerhead; for tasks that require more force, grip near its end.

- Let the weight of the hammer do all the work; with the properly selected hammer there is no need to apply your own force to perform the task.

- Swing from your elbow for power, and from your wrist for control.

- Focus on the piece being hammered, not the tool.

- Ensure the hammer face is always parallel to the surface being hit.

- Use repetitive, smooth blows; avoid sideways or glancing blows that can damage the surface being hit or the piece being driven in.

Safety Precautions When Using a Hammer

A hammer can become a very dangerous tool if not used properly. Follow the tips below to avoid injury to yourself and people around you:

- Use the right hammer for the job. Take the time to understand the different features of each model, head weight, or ask for professional advice related to your application.

- Select a hammer with a striking face diameter approximately 12 mm (0.5 inches) larger than the face of the object being struck (e.g., nail, chisels, punches, wedges, etc.).

- Always keep the striking face parallel to the surface being struck. Avoid side or glancing blows.

- Never use a hammer with a broken or loose handle. The head might detach from the handle causing injury.

- Never use a hammer with a damaged head, as it can damage the piece being worked on and cause injury.

- Always wear protection equipment (safety glasses, gloves, or face shield) when using a hammer.

How to Drive a Nail

- Grip the hammer in the middle of the handle, and hold the nail near the top between the thumb and forefinger of the hand not holding the hammer. If the nail is too small, use a piece of cardboard to hold it, while you hold the cardboard.

- Tapping the nail lightly until it has sunk enough to stand on its own.

- Using the centre of the hammer face, drive the nail in with smooth blows. Let the weight of the hammer do the work. The striking face should always be parallel with the surface being hit.

- When drilling nails into some hardwoods, it’s good practice to drill a pilot hole before you start hammering the nail. This method makes hammering easier and prevents wood from splitting.

I think gray tool are the best tool on the planet. They build quality tool&there Canadian made and engineer and made by Canadian. Wish there was more stuff made here in Canada

Thank you! I appreciate your content and find it a good source of education about hammers.